Written by author, James Willetts

Every film fan has one. That perfect film that if you had to choose one, would be your favourite. Doesn’t matter how often you say you couldn’t ever choose, that you have too many favourites, that you need to write a list. Not matter how often you say it, it’s not true. There’s always that one film.

Every film fan has them. Those perfect moments in a film when it just connects. Maybe it’s a perfectly written line, or an all too human facial expression, or just something that you’ve never seen anything like before, but this film has just blown your mind.

Every film fan has one. Those perfect cinematic experiences which elevate a good film to great. They’re not even anything to do with the film itself, it’s just because of when you saw it, or who with, or where. That film, those memories, will always have an attached meaning for you. They’ve transcended cinema. They’re part of you.

For me all those things describe one thing. Jurassic Park.

Sure, the opening to Star Wars IV: A New Hope had a bigger impact on me. Without that shot of the rebel blockade runner fleeing the Star Destroyer I would never have fallen in love with cinema.

And my perfect cinema experience is still Pan’s Labyrinth, sandwiched between a man who reeked of the sea and a woman who kept telling me what the Spanish words actually meant.

And all the others; staying up to watch Hercules in New York and Shark Attack 3 in hysterics, The Host and Rocky Balboa as a hangover cure.

All of these and more have had a profound impact on me, in ways that I can’t really put into words.

But above and beyond all of those, sits Jurassic Park.

And it can all be boiled down, I suppose, if it has to be, to a single shot. A single moment which, for me at least, is truly perfect. A moment that sums up everything that Jurassic Park as a film, that all films maybe, can be.

There’s so much there, though, so much more than that one scene. Spielberg often comes under fire for his sweetness, his inability to let a movie end without a happy ending. It can often feel jarring, even insulting, for a movie like War of the Worlds or AI to end in such a way, ignoring what has gone before, trying to tie everything up neatly. When it works though, it raises his films to greatness. His best films: E.T., Close Encounters, Raiders of the Lost Ark and Last Crusade, all contain the happy ending.

They are all, when it comes down to it, childlike movies. They are movies that seem filled with a childlike wonder at everything around them. It sometimes feels as though there are two Spielbergs. There is one who sees the world around him as it is, the one who makes Schindler’s List and Munich. But then there’s the one who makes Hook.

I think the reason that Spielberg is so well regarded is because he is the first filmmaker that anyone can recognise. That might seem like a self-defining trait, we recognise him because we know him. I mean it like this though. Before we understand the idea of Directors, or Producers, we know that there are some films that are made by certain people, defined by them in a way that there role in the actual film has little to do with.

All art contains the fingerprints of its creator. A Tim Burton film could never be mistaken as anything but. You can tell when Zach Snyder made something.

And before you knew who Spielberg was, you knew his films.

Those films that I mentioned are identifiable as his from the moment they start. The credit for at least part of that has to be laid at the door of John Williams, whose scores for Spielberg’s films have the same feel of instant recognition.

Certainly Williams lifts Jurassic Park. The main theme is instantly recognisable, a wistful and beautiful tune utterly in keeping with the backdrop of Isla Nublar. Where his theme for Superman and Indiana Jones was bombastic, joy filled and overblown, Jurassic Park is not about the people. Their triumphs and tragedies, whilst the meat of the plot, are secondary to the central idea of the film.

When it comes down to it, this is a classic Monster movie. A scientist, not mad but certainly eccentric, creates life. And just as in Frankenstein he is unable to control it. This theme, of man creating his own downfall, is one that runs throughout many horror films. From The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, via The Invisible Man and on to The Fly the idea of science gone wrong persists.

And as for the monsters themselves; boy are they good. Whilst the T-Rex is the obvious choice, it’s the raptors who emerge from the film as the real monsters. From their initial set up on the raptors are introduced and pitched to perfection, the xenomorphs of the dinosaur world. Smart, vicious and lethal they quickly establish themselves as the ultimate in predators.

It is only right therefore that the most celebratory moments of the film come from those times when we see the real stars, the Dinosaurs themselves.

As John Hammond’s greatest creation becomes his greatest enemy, his pride and near sightedness proves his downfall. That the body count is so low is testament not to the lightness of the proceedings but the light touch that Spielberg puts to what is essentially a horror film for children.

Gone are the dark shocks of Jaws. Gone the brooding, menacing score. In their place a lush, verdant setting and scares that thrill more than disturb.

For every dinosaur obsessed child, this was a film crafted for them. A film which celebrated that love.

When you see the Gallimimus run, or the raptors hunt you see every game that every child with a dinosaur toy has ever played. The T-Rex smashing a car over the edge of a cliff, or crashing through a wall to eat a lawyer. These are simple pleasures.

Testament to that is the care and attention that went into making the dinosaurs as realistic as possible. This is the last great film where the model and computer work are seamless. For a film made in 1993 those special effects still work. At 17 years old the film remains one of the greatest works of CGI ever made. No other film from that age stands up to similar scrutiny.

If the dinosaurs are the real stars it should not be forgotten that the cast is exceptional. Even the two child actors who are so grating now were, at the time, a joy to watch. To a 9 year old, the inclusion of a young boy with knowledge of dinosaurs that surpassed a palaeontologist was great.

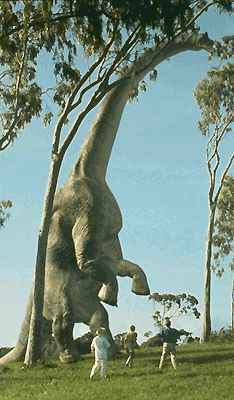

And all of that culminates in what is for me that single perfect moment. A moment that is scripted to perfection. As Williams’ score unfolds, we see for the first time a Brachiosaur. And we see two people who have spent their whole lives dreaming of a time they thought long past seeing it alive in front of them.

That moment, that dream come true, that shot of the Brachiosaur, stretching out. The pair of them geeking out over it. I can’t watch that without doing the same.

Somehow, that scene just works. That for me is magical. If anyone asks me to point out a single shot, to show just what can be done with a film it’s this I point them to.

That’s my perfect scene in my perfect film. The one that makes you fall in love with the monsters.

Beautifully written. A review with suspense and a happy pay off. Spielberg would be proud. Thank you.

Thank you very much! Glad to hear you enjoyed it.